How to Size a Kanban System: a Practical Guide to Get It Right

When talking about Kanban, the focus is often on the visual or operational aspects of the system: cards, racks, signage.

But what really determines the success of a Kanban system is something less visible, yet much more important: its sizing.

An undersized Kanban leads to stockouts. An oversized Kanban ties up capital and wastes warehouse space. Both situations undermine the benefits.

The key is to find the right balance, starting from a set of variables that must be carefully analyzed.

-

Understanding consumption: the first (and often underestimated) step

Every Kanban system is designed to satisfy a demand.

The first question to ask is therefore: how much and how do we consume this material?

Many companies start with rough estimates, such as the average consumption of the past months. But this simplification often leads to mistakes:

- The average consumption is simple to calculate, but it does not protect against small demand fluctuations.

- The maximum consumption guarantees safety, but results in an oversized and inefficient system.

- The most effective approach is to use statistical average consumption, which combines rigor and flexibility:

- Calculate a moving average of consumption over a time window equal to the lead time, and then use the 95th percentile of the averages obtained as reference.

- This builds a system that accounts for peaks without exaggerating.

This method provides a robust consumption value, not overly sensitive to daily variability but still able to react promptly to physiological demand fluctuations.

-

Lead time and safety lead time: the heart of the system

Once consumption is defined, it is essential to know precisely the overall lead time — the time between consuming a container and its replenishment, considering all phases (e.g., order reception, production, shipment).

In Kanban sizing, depending on the situation, the correct lead time must be considered:

- Purchase lead time: time between request signal and delivery by the supplier.

- Production lead time: time needed to replenish the card through internal production.

- Transfer lead time: for internal transfers between warehouses.

- Sales lead time: time between request signal and customer delivery.

The Kanban system assumes these lead times are constant and reliable.

If a supplier or internal work center cannot maintain stable times, the pull logic loses effectiveness.

A good practice, for example, is to formalize agreements with suppliers through supply contracts in the case of purchase Kanban.

Since suppliers (internal or external) may face problems or unexpected consumption may occur, a Safety Lead Time (SLT) is introduced.

Its purpose is to absorb possible delays or unforeseen peaks, improving the system’s overall reliability.

The SLT is not a fixed value, but must be defined according to system characteristics:

- A very reliable supplier with steady demand → low SLT.

- An unreliable supplier with variable demand → high SLT, with deliberate oversizing for protection.

-

Containers: an often-overlooked but crucial variable

The choice of container is not only a logistics issue: it has a direct impact on the sustainability of the Kanban system over time.

A key question to ask is: how many times per day can I afford to cycle a Kanban card on this item?

- If the container is too small, operators will be forced to handle frequent replenishments, impacting their operational activities.

- If the container is too large, the system becomes rigid, less flexible, and increases the risk of unused stock.

A best practice is to carefully assess container size. If consumption frequency is too high, use a second-level container:

- Instead of attaching a card to every single box, it can be linked to the pallet containing those boxes.

- This reduces rotation frequency while greatly simplifying management complexity, without losing pull logic.

Ergonomics is another key factor:

- Heavy materials require containers compatible with forklifts.

- Light materials can be managed manually.

- Warehouse layout and movement frequency must also be carefully considered.

-

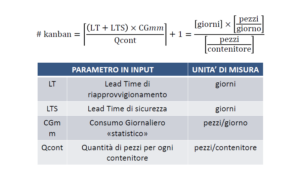

Sizing formulas: everything changes depending on the type of Kanban

Depending on the type of Kanban, the logic for calculating the number of cards changes.

Pure Kanban

The most classic form. Each container has its own card.

The number of cards is calculated as:

A safety stock can then be added, expressed in days or as a percentage.

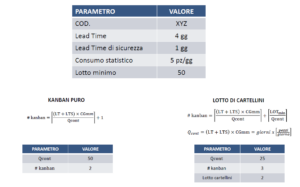

Lot Kanban

Used when suppliers or internal production work in lots much larger than actual consumption.

In this case, the formulas differ from pure Kanban:

The card circulates with each container, but the order is only released once a sufficient quantity is accumulated to generate the lot.

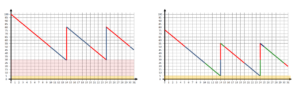

This approach reduces inventory, as shown in the chart below:

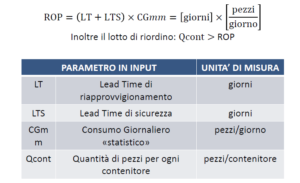

Signal Kanban

Kanban cards are always two.

There is only one case where a single card is used, placed at the Reorder Point (ROP): this is the Signal Kanban.

When stock drops below this threshold, a signal is triggered.

The formula is:

No number of cards is calculated here: the goal is to determine the point where the system must react.

Important condition: all material must be stored in one single location.

When sizing goes wrong

- Time is wasted

- Money is wasted

- Confidence in the method is lost

On the other hand, a properly designed system is robust, sustainable, and adaptable to change, provided it is correctly maintained.

Tools like KanbanRocket allow companies to automate these analyses and keep parameters always up to date, even in complex contexts with seasonality or trends.

comments